Top Ed-Tech Trends of 2014

A Hack Education Project

Buzzwords

Part 1 of my Top 10 Ed-Tech Trends of 2014 series.

It’s time once again for my annual review of the dominant trends in education technology. This is the fifth year that I’ve done this. It’s a massive undertaking, aided in part by the weekly roundups of all the education-related news that I write every week. It’s a project that I both dread – I mean, this is how I will spend December – and adore. I learn so much about the politics, industry, implementation, ideology, business, and bullshit by scrutinizing the year's occurences so closely. As someone who is fascinated by the cultural history of ed-tech, it’s always useful for me to see what stories are told most frequently and most passionately, what stories resonate and why.

A quick look back at previous year’s trends:

2010

- Ed-Tech Politics

- Online Learning

- Mobile Learning

- Social Learning / Social Networks

- Investment in Education Technology

2011

- The iPad

- Social Media – Adoption and Crackdown

- Text-messaging

- Data (Which Still Means Mostly “Standardized Testing”)

- The Digital Library

- Khan Academy

- STEM Education’s Sputnik Moment

- The Higher Education Bubble

- “Open”

- The Business of Ed-Tech

2012

- The Business of Ed-Tech

- The Maker Movement

- Learning to Code

- The Flipped Classroom

- MOOCs

- The Battle to Open Textbooks

- Education Data and Learning Analytics

- The Platforming of Education

- Automation and Artificial Intelligence

- The Politics of Ed-Tech

2013

- “Zombie Ideas”

- The Politics of Education/Technology

- Standards

- MOOCs and Anti-MOOCs

- Coding and “Making”

- Hardware

- Data vs Privacy

- The Battle for “Open”

- What Counts “For Credit”

- The Business of Ed-Tech

As you can see by this list, some things change; some things don’t. Indeed, last year I kicked off the series by arguing that what we often see in education technology are “zombie ideas,” monstrosities that just don’t seem to die.

Almost all of the trends I’ve identified in previous years continue to play some sort of role in the education landscape today. We haven’t resolved issues around data and privacy or around the high cost of higher education, for example. We’re still seeing schools struggle with social media and with 1:1 computing initiatives.

One programming note: Because the posts in this series tend to be so long, they actually break the technology of “the blog.” That is, I run up against the word count limit in my CMS. And I run up against the file size limit of feeds in Feedburner. For that reason, I’m going to post these stories into a GitHub repository and you'll be able to access them via GitHub pages at 2014trends.hackeducation.com. I’ll post a portion of each post here – the old truncated blog post thing – and you’ll have to click over to read the rest of the story over there. Sorry. That sucks, I know. Let it be a nice little reminder about how much technology sucks, and how we still can’t get the simplest things right.

All the Buzz about Digital Disruption

Education technology has become a bit of a buzzword in its own right. Or at least, if you put the adjective “digital” in front of an educational practice or a piece of educational content, then you can act as though you’re tapping into something profoundly new and transformative and, as the Obama Administration now calls it, “future ready.” That’s a boon for the education industry, no doubt, which has seen record levels investment into ed-tech startups this year (more on that in the next post in this series), despite reports of slower sales of digital (and print) materials. So much for predictions that ed-tech would handily “disrupt” the textbook publishers or other existing education companies. (Take the Trapper Keeper, for example. It now holds a tablet instead of spiral notebooks. And it costs a lot more too.)

Ah, “disruption.” It remains one of the buzziest buzzwords in education technology, alongside its partner word “innovation.” Silicon Valley likes to think of itself as having cornered the market (get it?) on innovation. That’s a core part of its ideology: innovation happens with tech and by tech and thanks to the technology industry – not thanks to the public sector. (My keynote this spring at the Canadian Network for Innovation in Education addressed this.) In February, for example, the Silicon Valley Education Foundation and NewSchools Venture Fund unveiled a Learning Innovation Hub to bring about innovation – or at least to help train educators on using ed-tech products. In April, the International Finance Corporation, the investment wing of the World Bank, set aside $20 million for investment in “innovation” through ed-tech VC firm Learn Capital.

In July, the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), known best in some education circles perhaps for its PISA tests, issued a report on “Measuring Innovation in Education.” In it, the OECD asks:

Do teachers innovate? Do they try different pedagogical approaches? Are practices within classrooms and educational organisations changing? And to what extent can change be linked to improvements? A measurement agenda is essential to an innovation and improvement strategy in education. Measuring Innovation in Education offers new perspectives on addressing the need for such measurement. [emphasis mine]

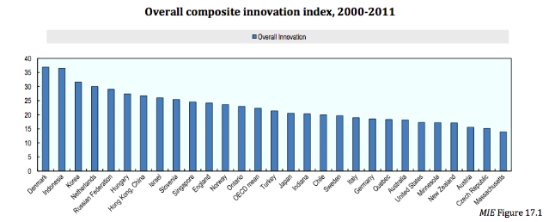

And here’s how countries rank — ah, the element of international competition — in terms of “innovation”:

The US’s ranking prompted hand-wringing headlines like “Report Finds U.S. Schools Rank Below Average in Innovation” and “Not Just the PISA: OECD Says U.S. Schools Also Behind on ‘Innovation’” — neatly confirming an education reform narrative that schools simply aren't “good enough,” and in this case, aren’t as “innovative” as the business sector. Moreover, schools need to become more like businesses in order to be more "innovative."

It’s worth asking how the heck you measure “innovation,” of course. Not surprisingly, the OECD measures it by looking at educational practices and policies that boost test scores.

Oh. Well then.

Without a doubt, Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen remains the biggest evangelist for “innovation,” or at least for his particular brand of innovation, “disruptive innovation.” He was a keynote this year at EDUCAUSE, higher education’s major ed-tech industry gala. While many other pundits have softened their predictions about the revolutionary potential for MOOCs, Christensen insists that “MOOCs’ disruption is only beginning.” And he’s doubled-down on his prophecy that, thanks to disruptive innovation, “half of universities will go bankrupt in the next 15 years.” (Mike Caulfield has graciously made us a countdown clock so we can keep track of the impending higher ed apocalypse.)

There’s been some pushback – and not just from me – on Christensen's whole “disruption machine.” That’s the headline from The New Yorker article published in June in which NYU professor Jill Lepore absolutely excoriates the concept and the whole narrative that’s been built up around it:

Most big ideas have loud critics. Not disruption. Disruptive innovation as the explanation for how change happens has been subject to little serious criticism, partly because it’s headlong, while critical inquiry is unhurried; partly because disrupters ridicule doubters by charging them with fogyism, as if to criticize a theory of change were identical to decrying change; and partly because, in its modern usage, innovation is the idea of progress jammed into a criticism-proof jack-in-the-box.

Christensen responded to Lepore’s article angrily, and in an interview with Bloomberg Businessweek, repeatedly called her “Jill” (not, say, "Dr. Lepore") even though he admitted they’d never met. There were similarly sexist responses from other powerful tech-bros. Tech bros – oh boy, was that ever a big trend this year. That's gonna be a great post in this series, just you wait.

Blended and Personalized: Words Drained of Meaning

As the frequent invocation of “innovation” and “disruption” highlights, there comes a point when words that might have had a specific meaning – “disruptive innovation” for example – get drained of all of that. Applied to every new product, every new policy, every new investment, the words lose their substance but, ironically perhaps, gain in significance. That’s how buzzwords work. They’re used to sound new and edgy and fashionable and perhaps fancy and jargonistic, but they lack a certain depth, I think, and a certain specificity. I read these words in press releases and in headlines and wonder, “What the hell are you even talking about?”

Two of the best examples of this: “Blended Learning” and “Personalized Learning.”

Sometimes blended learning means a mixture of human- and computer-based instruction. Sometimes it means that computer-based instruction is online. Sometimes the emphasis is on the different education technologies themselves – audio, video, adaptive quizzes, and the like. Sometimes blended learning is called hybrid learning. Sometimes it’s positioned as being a lynchpin to liberate the school system from “seat time.” Sometimes it’s positioned as something that gives the student more control. Or at least they can "move at their own pace." (And here, I mutter something about Papert and his reminder that we need to distinguish between the child programming the computer and the computer programming the child. Read Mindstorms, dammit.) Often blended learning is wrapped up with other rhetoric about technology’s connection to education reform. Sometimes blended learning is labeled as “disruptive.” That’s the argument that Michael Horn of the Clayton Christensen Institute makes in his 2014 book Blended: Using Disruptive Innovation to Improve Schools. (Horn was co-author with Christensen on Disrupting Class.)

The Christensen Institute has partnered with Silicon Schools Fund and with Khan Academy “to provide insight and guidance on delivering high-quality blended learning.” I still don’t quite know what “blended learning” means (or why it’s a good idea), but hey, they insist it’ll “personalize learning.”

Personalized learning. I always want to respond to this in my best Inigo Montoya voice, “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.”

On one hand, “personalized learning” sounds pretty good: a nod towards more student-centered learning perhaps, a move that honors the person learning not just the learning institution. But on the other hand, I do not think it means what you think it means. Often, what I see the term applied to gives me pause – “personalized learning” appears to be more focused on the scripting than on the student. Personalized learning isn’t personal learning. And often, it’s really “personalized instruction” – not focused on the person or the learning but on individualized delivery of standardized content and assessment. For some ed-tech industry folks, it's indistinguishable from “targeted advertising” even. So that's something to look forward to.

UCLA professor Noel Enyedy recently released a report on “personalized instruction” and the subtitle speaks volumes here: “New Interest, Old Rhetoric, Limited Results, and the Need for a New Direction for Computer-Mediated Learning.” What we’ve done is repackage an old model of what computers could do in education – again as Papert would put it, “ to program the child” – and simply label it something buzzy. There isn’t really research to show “personalization” will transform education. There isn’t really much proof it’s going to save school districts money (to the contrary). But it’s one helluva powerful buzzword.

Meanwhile…

Other notable education and ed-tech buzzwords: Efficiency. Efficacy. School choice. “Bite-sized lessons.” Adaptivity. “Everyone should learn to code.” Mastery-based learning (which is different from competency-based learning, a trend that I’ll explore in an upcoming post). Learning outcomes – in which you really really want to demonstrate “deeper learning.” Duh. Learning object repositories (one of last year’s “zombie ideas,” kept alive thanks in part by a renewed interest in them by LMSes. Thanks, team) which may or may not be related to “knowledge clouds.” “Interactive educational gadgets” – heck, anything “interactive.” That’ll probably boost “engagement,” whatever that means. “Open” (which I’ll explore in conjunction with MOOCs – stili a buzzword – and unMOOCs in an upcoming post). The “sharing economy” (which let’s go ahead and make very, very clear is utterly awful and exploitative and has little if anything to do with sharing). But hey, innovation! “Social learning” (which seems to often be code for “homework help” and “note-sharing” for students or “PD” for teachers). Digital natives (yes, people still use this phrase.) Behaviorism (okay, probably very few people call it “behaviorism.” They use some other coded language to describe it. "Classroom management" or something. Except this guy who boldly argued that B. F. Skinner will save us all.) Related, of course, to behaviorism is gamification – not to be confused with game-based learning or Gamergate or game-changers. Then there's grit. “Growth mindset.” Learning styles. Yes. Learning styles. Still. Sigh.

Buzzwords and Believability

In a blog post this year, Knewton CEO Jose Ferreira insisted that learning styles exist because “to me, it’s pretty obvious.” This is a perfect example of how buzzwords dovetail so neatly with believability. Even though there is no evidence that learning styles are real, the phrase is repeated so often, some people are certain that they must.

So much of education technology works this way. Blended learning, personalized learning, learning styles – they must be good because, after all, “to me, it’s pretty obvious.” A company releases a number, wraps it in a PR message, and as long as it fits the story we want to tell, it becomes the truth, widely repeated but never widely challenged.

One final ed-tech buzzword to demonstrate this: “brain training.” Plenty of startups raised venture capital this year promising to do just that, even though the scientific community – perhaps most loudly, the Stanford Center on Longevity and the Berlin Max Planck Institute for Human Development – have repeated that there’s very little supporting evidence that playing brain games and the like improves one’s cognitive abilities.

But we like the buzzwordiness of “brain training,” I guess. We find comfort in stories that our brains are fixable and flexible and that with the right technology we fill them more rapidly with words and concepts and learning and stuff. We find comfort in these stories even if they aren’t true. They feel good. They feel right. "To me, it's pretty obvious."

I mean, why stop and consider the science of learning or the history of ed-tech or its ideologies or its mythologies when we can rely on buzzwords instead? After all, buzzwords make the business of ed-tech so much better.

This was first posted on Hack Education on December 2, 2014.